Winning is underrated in grassroots movements

Why I think grassroots campaigns should focus more on winning over being bold

Grassroots movements can fall apart and die in many ways. One such way is having demands that are too broad, too intangible or have no defined endpoint.

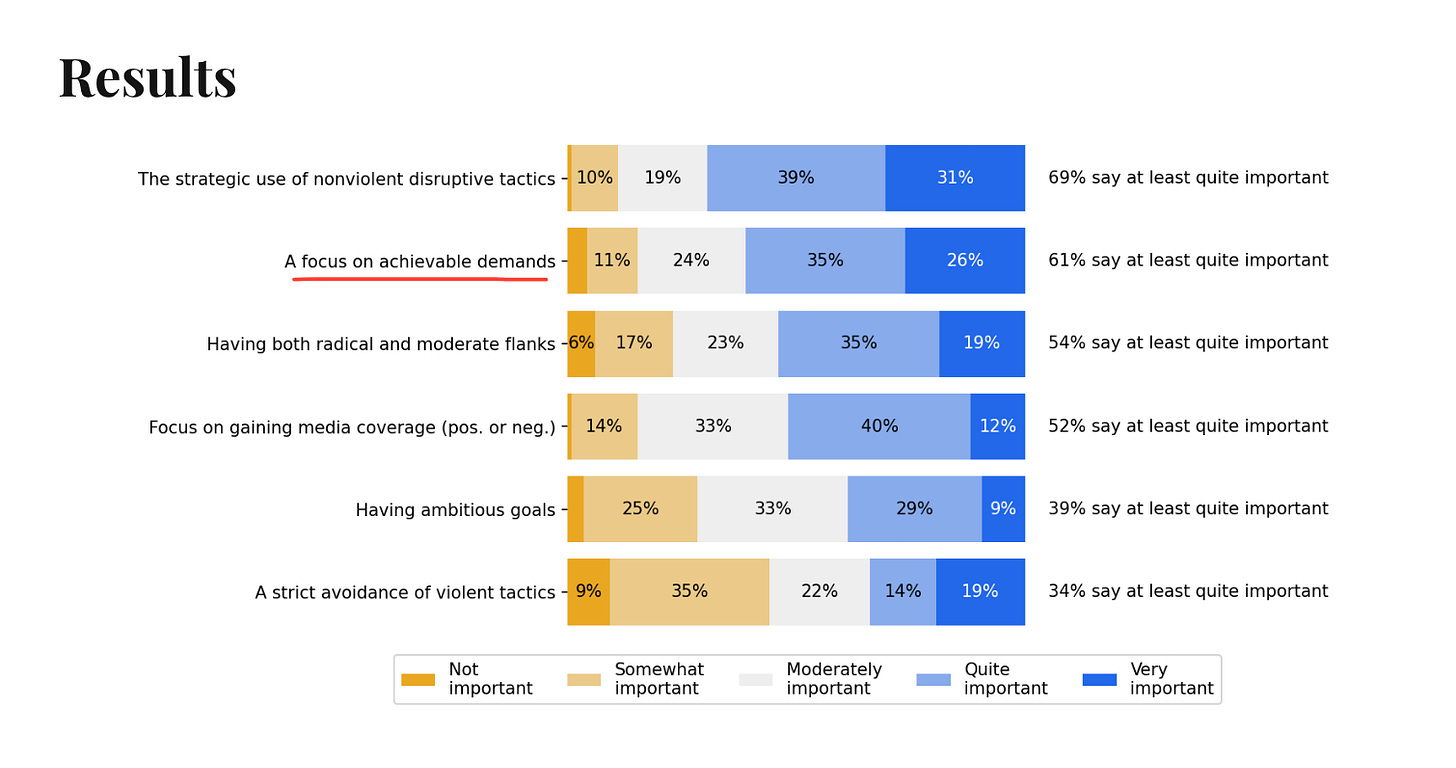

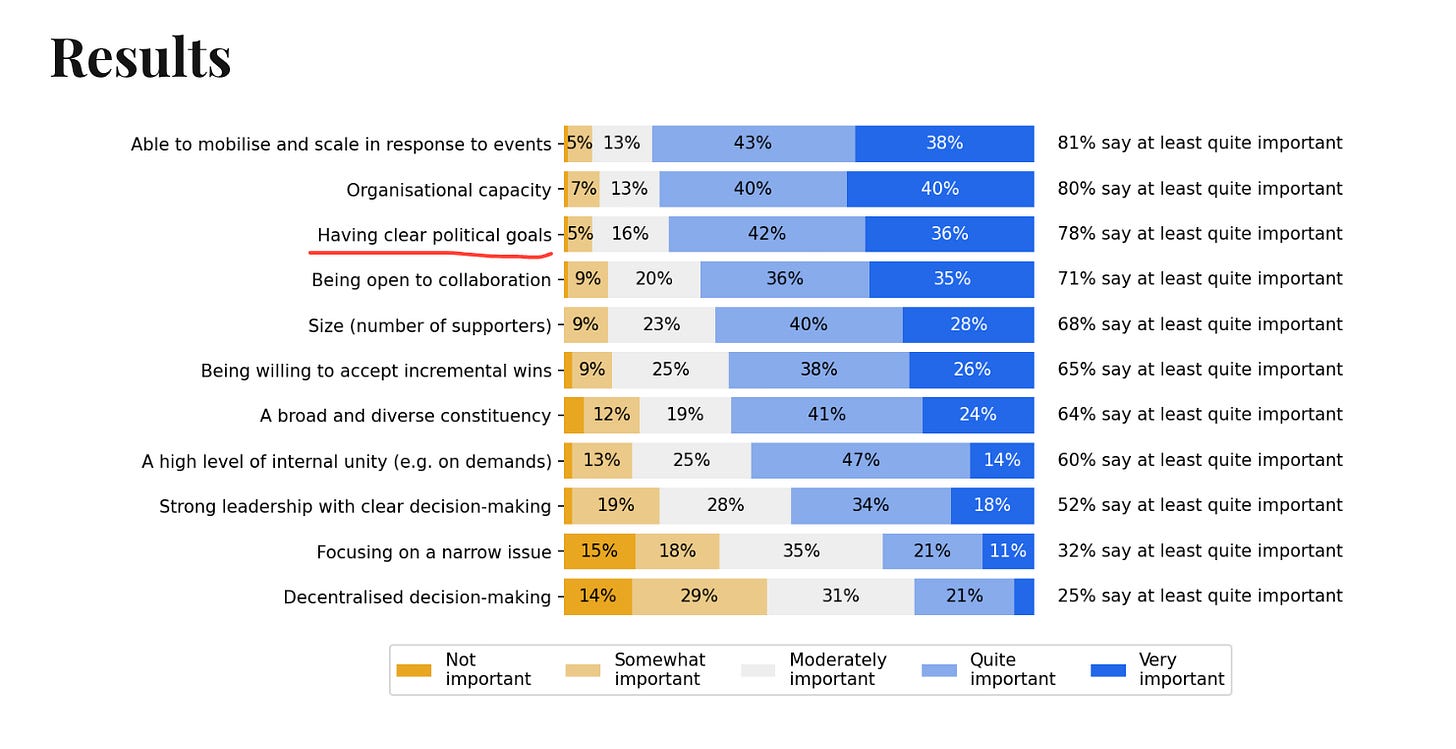

When Social Change Lab did a survey of 100+ political scientists and sociologists, something that cropped up was the importance of having achievable demands. In the graphs below, you can see that these experts believe that it was the 2nd most important strategic and tactical factor (of the ones we asked about) contributing to a social movement’s success. The second graph shows that experts also believed having a clear political goal was one of the most important organisational factors leading to success.

I wanted to unpack these findings a bit more, as it’s something that I think many grassroots movements can get wrong. It’s not easy to start a new social movement organisation or campaign focused on a big and important issue, such as climate change, anti-racism or animal rights. Similarly, it’s not easy to get the focus of your early campaigns right.

Let’s say you’re a new environmental group: Should you first focus on winning a ban on carbon-intensive advertising from your local city-level government, raise awareness about the multi-national factory farm polluting your local area or protest the lack of national-level action in your country? These decisions are hard and they matter a lot for the outcome of your campaign. But getting them right is crucial, and I want to especially outline the downsides of a lack of clear and achievable goals.

In summary, I think the following problems can arise without clear and achievable goals:

A lack of wins means you lose activists lose motivation and leave

People like joining winning campaigns

Defined campaigns build in natural cycles of intensity and rest

To expand on these:

A lack of wins is demotivating and demobilising

It may seem obvious, but it’s really hard for people to grind it out in campaigns or movements where they see little tangible progress. According to self-determination theory, humans desire competency, which is simply achieving desired outcomes and being effective in their actions. When you don’t experience this progress, activists can feel demotivated and drop out of social movement organisations. This is bad for a number of reasons. One, these are often people who have spent months or years building campaign experience, so you lose some of your most knowledgeable and well-connected people. Second, activist groups never have enough volunteers or organisers, so losing any individual is a meaningful loss. It also means that if your churn of existing activists leaving is too high, you will struggle to become a mass movement, which is a goal for many grassroots groups (and very correlated with success).

People like joining winning campaigns

Similar to the above, people like joining winning campaigns. If you want to grow, having some concrete wins under your belt is one of the best ways of doing so.

Dynamic social norms propose the idea that people are just interested in what everyone else in society is doing, but also the rate of change of everyone. This study shows that if people are told that more and more people are going away from eating meat, this is an effective way to encourage reduced meat consumption, even if the broader social norm in society is to eat meat. I think a similar thing happens in social movements: When you see a group achieve wins and rapidly expand, you want to get involved, even if it is a slightly risky thing to do. If you go to an induction meeting and there are a bunch of other new people with you, this provides legitimacy and some relief.

In short, I believe winning creates a virtuous cycle: win, attract more people, win bigger campaigns, and so on.

Defined campaigns build in natural cycles of intensity and rest

In addition to the mobilisation benefits mentioned above, I believe campaigns that are either clearly time-bound (e.g. due to elections, votes or ballot initiatives) or provide clear feedback by other means (e.g. a company policy, change in institutional behaviour, etc.) are important for reasons for seasonality.

In short, I find the concept of seasons of a social movement (see their video on this here), developed by Ayni Institute, quite interesting. The idea is that social movements experience seasons, where spring may represent the growth of a new grassroots group, summer is a busy period of mobilisation and action and then autumn might be the time to celebrate victories, regroup and reflect.

I’ve come around to thinking that if campaigns don’t build in some cycles of intensity, followed by rest, then it’s a fast track to burnout for activists. So choosing a clearly defined or time-bound campaign naturally builds in these periods of rest and intensity. It can be possible in other ways but in my view, this is the simplest.

What are some tangible examples of a well-targeted campaign?

So, what does a well-focused campaign actually look like in practice? One example is the pair of ballot initiatives in Denver, run by Pro-Animal Future, to ban slaughterhouses and the sale of fur within Denver (read more about those campaigns here, here and here). There is a similar campaign to ban factory farms in Sonoma County, run by Direct Action Everywhere, which you can also learn more about here.

I’m excited about this campaign as it’s extremely tangible: come Election Day on November 5th, people will go to the ballot box and vote. These initiatives will either pass or not – there is no confusion there. Additionally, even though it's specific and somewhat “small” (we're talking about a single city's laws), it's still inspiring enough to get people fired up about animal advocacy more broadly. Plus, you can see your progress - every signature collected, every voter convinced, every council member who comes on board is a tiny win along the way that can be celebrated.

Another very different example is Just Stop Oil in the UK. Their goal, as you might expect, was to stop the licensing for new oil and gas exploration in the UK. The climate movement in the UK was pretty strong so it had the ability to have this fairly ambitious and symbolic target as a genuinely winnable campaign. And behold, the Labour Party did commit to this before they were elected and they confirmed this when they took power a few months ago. They’ve since moved onto a new demand, asking the UK to “work together to establish a legally binding treaty to stop extracting and burning oil, gas and coal by 2030 as well as supporting and financing poorer countries to make a fast, fair, and just transition.”

But Wait... What About the Big, Bold Movements?

Now, you might be thinking: "But what about movements like Extinction Rebellion or Occupy Wall Street? They achieved significant impact without highly specific or achievable demands." This is a fair point which I think is worth covering. These groups had goals like “Net Zero by 2025” in the case of XR, which would be almost literally impossible to achieve, and Occupy even refused to have specific demands so they could talk about economic inequality and corporate influence more broadly.

However, groups like XR have indeed been successful at shifting public discourse and the Overton window around climate change (see some previous work I did on this here). Occupy Wall Street fundamentally changed how we talk about economic inequality (e.g. how "we are the 99%" entered our collective vocabulary). These movements demonstrate that sometimes, broader, more symbolic actions can catalyse important social conversations.

However, there's a crucial drawback of these more symbolic goals: these groups often struggle with longevity. In my experience, without concrete wins to sustain motivation, these movements tend to experience a high turnover of volunteers and soon enough, declining participation. This doesn't make them failures - shifting public discourse is valuable (and XR did achieve some very concrete wins too) - but it does suggest that different approaches might be needed for different stages or aspects of social change. For example, once groups like Extinction Rebellion have done the groundwork of establishing climate change as a key issue in the UK and shifting discourse, Just Stop Oil can step in to achieve some tangible legislative victories.

So, it does take some thinking to understand what stage of your issue you’re at, and how you should strategise accordingly. However, for almost all groups no matter your strategy, I'd encourage asking yourself these questions:

Can we clearly articulate what winning looks like?

Do we have meaningful milestones along the way?

Are our goals ambitious enough to inspire but achievable enough to maintain momentum?

Have we built in natural periods for rest and reflection?

The answers might lead to refining campaign goals or even choosing different targets entirely. But in my experience, the time spent getting these fundamentals right pays dividends in building sustainable, effective movements.

Great piece. I've been thinking about this a lot recently and feel like the movement could benefit from much more strategic and intentional growth of supporters. Typically, it feels like groups design their campaign solely on what they want to achieve and then go and find or hope they have the supporters on the journey to get there, rather than building a campaign(s) around moving people into increasing stages of willingness to support (via smaller wins) to build a more powerful momentum. In a way, we're back to front. Start with where you need to get to and build the momentum towards it (probably over years), rather than set a final destination and just keep pushing (and losing people along the way).

Thanks for another great write-up. It is interesting that you bring up the US 2024 ballot initiatives (Denver (x2), Sonoma, Berkeley). Of the 4, only Berkeley won. These campaigns have touted successes besides whether voters approved the initiative, and DxE has even acknowledged that the factory farm ban initiative in Sonoma was intentionally overly bold, with a willingness to not win the initiative yet still gain knowledge of opposition tactics and grow public awareness. I suppose this needs to be balanced, as you bring up, with member retention and movement sustainability.