Megaprojects for Animals + Public Opinion Polling on climate protest!

Two very different but equally exciting things to share today

Hello! I’ve been slightly underperforming in writing something every 2-4 weeks, but there’s two pieces in this article + one to come shortly, so hopefully that compensates. The two pieces in this blog/newsletter are:

Megaprojects for animals - Neil Dullaghan (from Rethink Priorities) and myself explain why megaprojects (projects that can cost-effectively use $10m+) might be important to think about. In addition, we brainstormed and categorised a long list of these ideas, with great contributions from friends & colleagues

Disruptive climate protests in the UK didn’t lead to a loss of public support for climate policies - Through my work at Social Change Lab, myself and Sam (my colleague) found that disruptive protests by Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion didn’t lead to a “backfire” effect i.e. there was a loss of support for climate policies. In addition, there’s some weak evidence that it actually increased the number of people who are likely to take part in climate action. There was a bit of drama in our findings here so I encourage everyone to read about it below!

Megaprojects for animals

On the megaprojects article, I don’t have too much more to add besides check it out! Megaprojects get a fair bit of attention within longtermism (e.g. here, here, here, here, here, here) but not yet really within animal advocacy. The question we wanted to examine was: do we have similarly scalable and promising opportunities to cost-effectively help animals given additional financial resources?

This is something I think about a lot, as it seems like EA donors are doing reasonably well, and that grantmaking is increasing somewhat quickly. However, it’s not obvious that the opportunities we currently fund to help animals have the ability to cost-effectively absorb 2-3x more donations, which could happen. So our driving motivation was: What are some potential large and effective projects if our current projects become fully funded or less cost-effective? What options do we have for other species and welfare asks? Can they scale?

For the rest of the article, which is basically lots of exciting ideas, go read it on the EA Forum!

Public Opinion Data from climate protest

I’ll talk about some particularly interesting bits below, as you can read the more comprehensive analysis here.

In short, through our work at Social Change Lab, we commissioned YouGov to conduct three nationally representative surveys of approximately 2,000 people each in the United Kingdom, focusing on their views on climate change, their willingness to engage in environmental activism, and their opinion of the climate activist group Just Stop Oil. Our key results were:

Despite disruptive protests, there was no loss of support for climate policies. We believe this provides some evidence against the notion that disruptive protests tend to cause a negative public reaction towards the goals of the disruptive movement.

There was a marginally statistically significant change (p = 0.09) in the self-reported likelihood of participants taking part in environmental activism from before the protests to after the protests. Whilst this is slightly outside standard scientific margins of error, we think it’s still worth reporting weak evidence which readers can interpret for themselves (see more here).

Attention to the actions of Just Stop Oil was significantly lower than previous campaigns, such as ones by Insulate Britain or Extinction Rebellion, by an order of 4-33x. We think this was largely due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. We believe this factor also significantly reduced our effect size, as most of the impact of protest is via media coverage.

Due to existing high levels of climate concern in the UK, it’s possible that broadly trying to increase concern for climate change is now less effective than it was in previous years. One might infer that it’s now more promising to focus grassroots attention on building salience for more neglected issues (e.g. clean energy R&D), advocating for issues that are particularly tractable, or on focusing on climate advocacy in countries with much lower baseline support for climate change.

So what was particularly interesting throughout this research?

We had to change our conclusions based on feedback

Initially when we did this research, we excitedly announced it on Twitter saying we found a statistically significant (p < 0.05) result that climate protest had likely increased the number of people willing to take part in climate action. Since then, we had feedback from one person that we might be falling foul of multiple hypothesis testing. Basically, if you’re testing 100 hypotheses at the same time, then purely by chance you will find 5 hypotheses that aren’t true but are still are statistically significant (p<0.05). If you want to see a funny comic explaining the problem via jelly beans, you can do so here. I checked with a statistics and survey expert about this, and they reassured me that for our survey it was very unlikely to cause a change and it was okay if we didn’t correct for this. However, we got some more feedback from another reviewer that this might be a problem. To nip this in the bud, we decided to do the additional checks anyway to make sure it really wasn’t a problem….and it was!

In short, when we applied additional corrections to account for multiple hypothesis testing (the Benjamini-Hochberg corrections to be precise), this made our p-value drop to p = 0.09, outside standard scientific margins for error. How frustrating! Whilst it was sad that our findings changed, in good faith we couldn’t ignore this so we updated this in our findings and I published a new Twitter thread explaining the situation. Whilst this means there is now a 9% likelihood of our finding being chance rather than our original 2%, we still think this is valuable evidence that readers can interpret for themselves. So, what did I learn (or re-learn) from this weird and stressful two weeks?

Experts can provide very contradictory advice

Speaking to 2-3 different experts we saw how different people offered reasonably differing and contradictory advice, even if they were both (in my eyes) very competent folks. This definitely didn’t make our job any easier when deciding how to conduct our analyses and present or results. Ultimately, we had to use our own judgement to decide who we should defer to and trust more, which isn’t always straightforward.

Statistics is surprisingly subjective. There were several technical questions we had where we got different answers, depending on who we asked:

When to correct for multiple hypothesis testing and when to not (our first and main issue)

When to stick to your pre-registration or change things slightly if you’ve identified a flaw in your method (e.g. multiple hypothesis testing wasn’t in our pre-registration)

Which multiple hypothesis correction method to use when: Do we use Benjamini-Hochberg, Benjamini-Yekutieli or something else altogether?!

How to report results that have a p-value greater than 0.05 but less than 0.10 e.g. ones that are marginally significant.

This experience also made us realise that our effect size was much smaller than we anticipated, which might be a reason why our significance level was higher too. In brief, if you have a small effect, it’s hard to pick up significant changes even if they are really there, due to limited sensitivity of your sample size. I was already aware that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was dominating news coverage so had relatively low hopes for Just Stop Oil & XR media coverage in April, but it was still lower than I expected. Decreased media coverage is important, as most of the impact of protest is mediated via the media. Therefore, it’s very reasonable to assume that less media coverage leads to less impact, something which we believe happened.

2. Media coverage was much lower in our survey period relative to previous campaigns

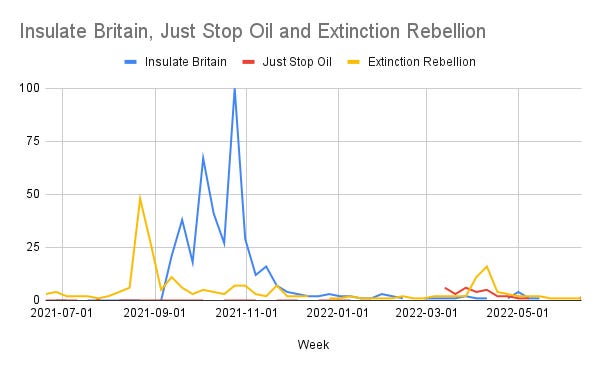

So, was media coverage of Just Stop Oil and XR in April 2022 actually lower than previous similar campaigns? And if so, by how much? Some naive estimates of this can be made using Google Trends data, as seen below.

It might be hard to discern exact figures from this chart, but Just Stop Oil in April 2022 got roughly 3% the Google search volume that Extinction Rebellion did in April 2019, when similar research was conducted that did find significant shifts in public opinion.

Of course, we might say April 2019 was an outlier as it really was an exceptional boom in the global climate movement, but we can also compare the recent campaign we surveyed to Insulate Britain in September 2021. As seen below, the combined activities of Just Stop Oil and XR still only received 25% of the search volume Insulate Britain did in October 2021. Now there might not be a perfect correlation between Google search volume and media coverage, I do believe they’re fairly well correlated.

Due to these factors, it’s quite plausible that our effect sizes could have been bigger and therefore easier to detect, had their been more media coverage and attention around Just Stop Oil. However, we do think the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a one-off, and mainly unfortunate that we had our polling scheduled for then. We hope to run similar polling in the future, which hopefully won’t have this complicating factor.

3. We might be reaching diminishing marginal returns for some issues

Whilst potentially controversial, our findings here might suggest that we’re approaching diminishing marginal returns to doing certain kinds of protest (what we call the “ceiling effect” in our report).

For example, it's very plausible that UK public opinion on climate issues is already so high for certain variables, marginal increases are quite hard to elicit. This is discussed briefly in Kenward & Brick (forthcoming), where “concern for climate change” had a mean response of 5.3 out of 7 initially, meaning there is little scope for this to increase. As the salience of climate issues has increased dramatically since 2018, it’s plausible that there are now diminishing returns on climate campaigns where the main outcome is high levels of media coverage, as most people interested in climate issues in the UK have likely already been exposed to relevant news and information. It’s important to note that a large increase in concern for climate change may have occurred due to the work of Extinction Rebellion, Fridays for Future and other grassroots groups, as explored both here by YouGov and here in our previous work.

To illustrate this ceiling effect, in our ‘Before’ polling we found that the mean score of “concern for climate change” was 4.8 out of 7 and the public awareness of the impacts of fossil fuels on climate change was 5.1 out of 7, implying high existing knowledge of the issues that Just Stop Oil was trying to draw attention to. A caveat is that we believe this is potentially only relevant to the UK and a select few other countries, specifically those with the highest percentages of public concern for climate change globally.

One potentially large implication of this is to prioritise (potentially disruptive) climate protest and campaigning in countries with relatively low levels of concern for climate change, or, if protesting in countries who already have high concern, focusing on specific issues that have less public salience, or are particularly winnable. In short, the need to be strategic is now more important, and simply raising awareness is likely not that useful.